Plant mimicry has always been a rather select field, both in nature and in scientific study, though not necessarily uncommon in the former. This selectivity is due to the fact that it serves no direct benefit in the battle between different plants for sunlight or other sorts of land superiority. Instead, before humans, mimicry of this kind was reserved for tricking the, usually insect, partners of certain species of plants in order to make them think another type of plant was the one they desired.

This was commonly utilized as a method for plants to spread their pollen and reproduce more widely. But, as you can tell, it is a niche field and almost always only applies to the flowering plants, if at all.

Arriving On The Scene

However, ever since the introduction of humans onto the scene, things have changed wildly. We were and are, in a manner of speaking, a being of order and uniformity. We brought form out of the chaos and conflict that is life. That is because for something like plants and agriculture to be useful to us, we need a certain amount of reliability, predictability, and constancy to be involved in the growing of them.

This created a change within the system of natural selection. At least for the plants we grow and the other organisms that interact with them. We selected the random mutations and the traits spawning from them that benefitted us, causing a desired and purposeful change that was not directly to the benefit of surviving in the wild. For the, often open and plains-like, land we chose to grow our crops in, this created a problem or perhaps an opportunity for the plants we commonly term weeds.

These non-crop plants still wanted to grow on that land, but we had the tendency of pulling them up when we found them. This proved an issue for a while. Then the weeds came up with a clever trick.

But, before we get into that, let’s go over the topic of weed mimicry as a whole first and some other kinds of mimicry before getting into the particular type that is a more direct focus of this article.

The Background of Mimicry

A Lack of Scrutiny

The research available on weed mimicry is surprisingly sparse. Almost all of the recent efforts have focused on specific cases around the world, rather than looking at the topic in an overview. Perhaps this is because mimicry is fairly far down the list of problems in agriculture? Maybe so.

Due to this, most of the basic overview information on the topic was put out in succession in the 1980’s by a handful of scientists. You can see basically all of those listed in the reference list below and, lacking other more contemporary sources for general information, we’ll have to settle for those. Hopefully they are not too out of date, but it seems like they probably aren’t.

The Fight’s Progression

There are a lot of selective forces at play in agriculture. Not just directly from humans in the form of handweeding and pesticide usage, but also from the type of crops being grown, what kind of land it is being grown on and the soil quality, along with how the environment has changed around these regions over the eons.

And I should start off by noting that it’s not as if weeds are wholly resistant to these forces. In fact, human efforts have been largely successful in eradicating the pest plants that sprout in our fields. Entire species have been nearly wiped out over the centuries, especially as our crop growing methods have industrialized and better tools have been made to improve our ability to fight against pests.

Those that remain are the most intractable of the bunch, the ones that were at least partially successful at developing some sort of resistance trait that allows them to survive. In recent years, this has often taken the shape of herbicide resistance, but there are many more options than just that.

Taking Advantage of Growing Methods

For example, some weed species have taken advantage of our use of fertilizer and the particular types of chemical nutrients found in such applications. They have specialized their root intake structure to pull in those particular nutrients quicker and to grow faster than they normally would, giving them a chance of passing on their genetic profile before being pulled from the ground.

Another form of resistance and which could perhaps be termed a type of mimicry comes with the crops that are grown in off-years. One year of crop growing is followed by a year of fallowing and animal grazing to let the soil recover. Some weed species have evolved so that they too only grow in the years that crops are planted, to take advantage of the extra nutrients available then and to avoid being preyed upon by the aforementioned farm animals.

A similar system has shown itself seasonally with farmers who routinely plant the same types of crops at the same times of year. The weed species will purposefully mimic and match their growing times to that of the farmers. This is especially useful for weeds that grow in rice paddies, as growing in the wrong season could put them high and dry without adequate water.

All of those make up ways for weeds to try and pass on offspring without being killed by humans. Some try to do things fast before they can be killed and others try a different tactic. Let’s talk about the latter.

Vavilovian Plant Mimicry

Cut Down In His Prime

Now that we’ve got some of the basics out of the way, we can focus on the prime subject of interest. Vavilovian mimicry is named after the titular Nikolai Vavilov, a former resident of the Soviet Union. He was a brilliant biologist and a leader in the field of plant research. Unfortunately, his scientific research and focus on scientific rigor in the subject of genetics over all else put him at odds with the leader of his country, one Joseph Stalin.

The refusal of Vavilov to kowtow to the pseudoscience pushed by the praised Lysenko was his unfortunate downfall. Vavilov, while keeping to his stance on the true facts of genetics and breeding and how evolution functions, was summarily imprisoned in a gulag and died not long after in 1943. If you wish to know more about him, I highly recommend the first reference in the list down below.

The Terms We Employ

One of the primary things Vavilov discovered was that certain common crops grown today, such as rye (Secale cereale), were originally considered weeds by crop growers. Their attempts to destroy them directly led to their incorporation under the label of agricultural crop. How did this happen, you might ask? Well, it has to do with location, climate, and mimicry. But we’ll get to that.

When discussing plant mimicry, there are three specific jargon-defined terms that must be understood. The first is the model, which refers to the particular crop or plant being mimicked. The second is, you can guess, the mimic, which is the weed species in question. And the third is the most important term of the three, it is the operator. This specifically refers to whatever the deciding force is in regards to selection. This can be a human, an animal, or even just a machine. Whatever it is that decides whether an organism is the desired crop or an undesirable weed.

What weeds took advantage of is the fact that the discriminatory abilities of humans are limited. We are only so good at determining whether a crop is a crop or not. If we did genetic testing every time before we picked anything, then the issue would be moot, but we (thankfully) don’t go quite that far yet.

Making A Crop From Thin Air

Vavilov recognized that the long term evolutionary prospects of selection pressure from humans would naturally drive the weeds to take one of the only options available to them. Sure, some would go the route of thick, fibrous roots that make it incredibly difficult to pull up the weeds and others might even try and make themselves painful to touch, whether by pinprick or by chemical means. But enough others would go the route of tricking us directly. Since fooling our eyes is no big feat.

In fact, it is not even too difficult of a prospect for the weeds themselves. All they are doing is changing their phenotypic expression, how they look on the outside. In comparison to some other types of genetic changes, just changing how they look on the outside is a cinch. And, as random mutations led to better and better mimics surviving over time, the selection pressures by human farmers would eventually turn the weeds into a near identical lookalike to the crops themselves.

Their genetics would still be profoundly different, but all that means is that they are a separate species of now arable land growing crops. Thanks to this nearly perfect recreation of other plant species, Vavilovian mimicry is sometimes also called true mimicry. Since it is actively mimicking the actual visual being of another organism.

Crypsis: The Mimicry of Everything

Mimicking Parts

As an aside section for a moment, it should be pointed out that creatures able to blend into their surroundings, like chameleons do, are not an example of this type of mimicry coined by Vavilov. Instead, they are utilizing what is called crypsis.

This is a form of mimicry specifically where the operator (remember our terminology before?) is unable to distinguish the organism from the other things around it. This is fundamentally different from the operator confusing an organism as another organism. Any type of species that can either change its color or grow parts that look like commonly growing plant parts fall under the category of crypsis. The most commonly grown structure for such mimicry is the shape of leaves. Many insects take this path either as a way to avoid predation or to actively conceal themselves for preying on others.

But even weeds can use crypsis to their advantage. Certain vining plants can twine around a crop and grow leaves that look just like the host plant they are using. This isn’t the same as them pretending to be an entire separate copy of the plant. Instead, they are, in a manner of speaking, making themselves a part of the plant.

Hiding In Plain Sight

This tactic has some advantages. Weeds that use Vavilovian mimicry as a safety mechanism really have to be perfect or they’ll be found out. And such perfection, even now, is rare to find. Especially since farmers actively seek out such weeds to remove from their fields. Heck, even if they were the crop themselves, if the plant is growing outside of the set rows made by the farmer, it’s likely to be uprooted anyways.

Because of that, crypsis may be the better choice in some cases. If done well, they are actively concealed by being a part of the proper crop plant itself and are in the appropriate growing location that the farmer expects. The only real risk is a random check by the farmer on that particular plant finding them out, but that is a far better chance for their survival than the other options available.

Rye’s Crop Evolution

Going back to the main topic of Vavilovian mimicry, let’s return to the case of the successful integration of the weed known as rye into the crop system. It was perhaps a lucky chance and synergism between human activities and location. Just because rye began looking almost identical to wheat and other such crops doesn’t mean it would then be actively used as a crop itself.

Farmers would have no need to and certainly little desire to have to domesticate yet another crop and all the effort that would entail. They already had feasible crops to grow, why add more? But then something changed. Humanity continued to spread and one of the directions it walked in was north. The cold and freezing north inhospitable to life, also known as Europe.

What happened when they got there was nearly a disaster. The wheat and other crops that they planted refused to grow in the low temperatures. They would have been on the verge of an outright famine if it wasn’t for some sneaky rye seeds that had snuck along with their wheat containers. These seeds had no problem with the temperatures and grew strong and tall from the glimpses of sunlight they got in the summer.

It was a simple step from this discovery to rye becoming a direct staple of European agricultural economies. And thus a weed became a crucial crop that saved the northern society. Of course, the whole thing was a lot more complicated than just that, but you get the basics.

Vavilovian Seed Mimicry

Tricking The Automatons

So, we’ve discussed how Vavilovian mimicry in its more direct form is done, but there is another side to things that has only been alluded to up til now. And it is actually possibly the more common variety, thanks to the pressures of modern technology.

That is seed mimicry, And it is more widespread because it is simpler than trying to fool the critical eye of a human being. All it has to do is fool the threshing mechanism of the combine. For all the monotonous scrutiny that machines can put forth in their activities, they are still currently not able to tell things apart beyond basic features. It is thanks to this that the weeds can take advantage of these checked traits.

An example of this is the balloon vine plant (Cardiospermum halicacabum), whose seeds match the shape and weight of the seeds from the soybean plant (Glycine max). This has given no small measure of headaches to harvesters of soybeans and the balloon vine is commonly referred to as a pernicious pest of soybeans thanks to this capability of being swept up in machine-based harvesting and planted the following season by yet more machines.

Operator-Based Evolution

This opposite type of mimicry to plant mimics is all thanks to a change in the targeted operator. Rather than humans putting the selection pressures on weeds that result in only the ones better suited to blend in surviving, the pressures in many countries around the world today are placed upon the plants by machines. It is the machines that do the collection and separating of proper crop seeds from other plants that are swept up.

With a machine as the operator, the selection pressure changes and this results in a very different type of weed mimicry forming. And it’s not like there’s just one operator or one kind of pressure working at a time. In most cases, there are several things that the weeds are selected against, including herbicide tolerance and climate change. The operators for each of these are different and require different random mutations in order to survive against. But some weeds manage it.

Even the simple act of mowing grass exerts its own type of pressure, changing the type of plants that grow in the grassy area and to what height they grow. Weeds can survive by growing in seasons unlikely to experience mowing by humans and also by sticking close to the ground to avoid the clippers of the mower.

This can also take the case of weeds growing to look like shortened pieces of cut turfgrass, protecting them even further from inspecting eyes. The results of selection pressures and random mutations can be surprising and amazing and the world of mimicry is one of the best examples of those capabilities.

A Continued Selection

With all of this to consider, it really gives a new light to what plant mimicry can do and how even with advancing technological progress, it remains difficult to advance in dealing with pests and weeds. For every new technique and maneuver that may be developed by humanity, there is a countering answer from the weeds themselves.

Even automation does not appear to change anything significantly, it just creates new avenues for plants to take advantage of. This is especially so thanks to the repetitive and unchanging nature of how machines conduct themselves, meaning that the operator is not a constantly changing or reactive enemy, but a static one. All in all, that makes things much easier for weeds.

I hope this breakdown of the types of plant mimicry has informed you on what plants and natural selection can accomplish. I do sorely wish that more research will be focused on this small area of biological mechanics, since it is truly one of the bases of reactionary evolution and the driving of resistance to environmental pressures.

References

1. McElroy, J. S. (2014). Vavilovian Mimicry: Nikolai Vavilov and His Little-Known Impact on Weed Science. Weed Science, 62(2), 207-216. Retrieved July 16, 2017, from http://www.bioone.org/doi/pdf/10.1614/WS-D-13-00122.1

2. Wainwright, B. (2016/2017). Where have all the plants gone? A review of plant camouflage strategies. Retrieved July 16, 2017, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Benito_Wainwright/publication/317389207_Where_have_all_the_plants_gone_A_review_of_plant_camouflage_strategies/links/5938905da6fdcc58ae6314f4/Where-have-all-the-plants-gone-A-review-of-plant-camouflage-strategies.pdf

3. Zamora-Meléndez, A. (2010, May). Genetic Diversity And Evolution Of Disease Response Genes In Sorghum Bicolor L. Moench And Other Cereals. Retrieved July 16, 2017, from https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/17188/Zamora-Melendez%2c%20Alejandro.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

4. Fried, G., Chauvel, B., & Reboud, X. (2015). Weed flora shifts and specialisation in winter oilseed rape in France. Weed Research, 55(5), 514-524. doi:10.1111/wre.12164

5. Barrett, S. H. (1983). Crop mimicry in weeds. Economic Botany, 37(3), 255-282. Retrieved July 20, 2017, from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02858881.

6. Williamson, G. B. (1982). Plant mimicry: evolutionary constraints. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 18(1), 49-58. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1982.tb02033.x

7. Barrett, S. H. (1987, September). Mimicry in Plants. Scientific American, 255(9), 76-83. Retrieved July 20, 2017, from http://labs.eeb.utoronto.ca/barrett/pdf/schb_54.pdf

8. Vane-Wright, R. I. (1980). On the definition of mimicry. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 13(1), 1-6. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1980.tb00066.x

9. Ruxton, G. D., Sherratt, T. N., & Speed, M. P. (2004). Avoiding Attack: The Evolutionary Ecology of Crypsis, Warning Signals and Mimicry. Oxford, UK: OUP Oxford. Retrieved July 20, 2017, from https://books.google.com/books?id=P38SDAAAQBAJ

10. Radosevich, S. R., Holt, J. S., & Ghersa, C. M. (2007). Ecology of Weeds and Invasive Plants: Relationship to Agriculture and Natural Resource Management (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved July 20, 2017, from https://books.google.com/books?id=2paeqsOV2I8C

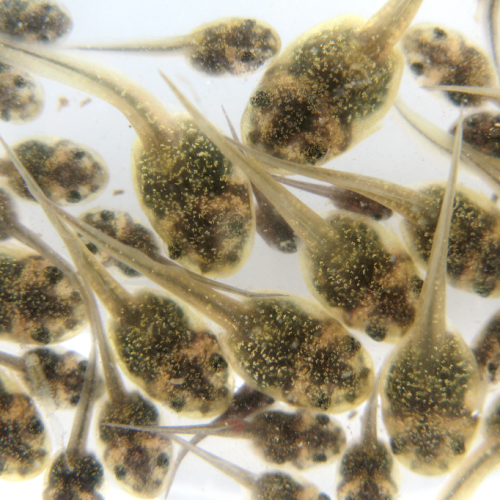

Photo CCs: Five weed mix from Wikimedia Commons