Evolutionary history can often provide profound insights into genetic switchups in our past that may continue to hold a significant impact on our lives today. Thus, breaking down the genomes of our shared ancestors with other species and points of divergence is a primary area of research in biology.

The Sialic Sugar Family

The disparities between humans and other animals is sometimes a huge gap to bridge and, at other times, so close as to be species compatible. This is true in discussions of health and nutrition, along with research areas like xenotransplantation that involve using animal organs in human bodies or studies that use model organisms to replicate patterns of disease in humans. In these cases, it is a prime directive for us to understand just how close we are to the animal being used in order for our experiments and procedures to be successful and accurate.

Such ideas have led researchers at the University of Nevada, Reno to focus on a particular member of the sialic acid family. This group is made up of nine carbon chain sugar compounds that are found to be distributed across the tree of life, from animals to plants to fungi and insects. Overall, they appear to have developed alongside the formation of higher multicellular life forms and, for animals like us, are involved in the brain to facilitate neural transmission.

Otherwise, they are frequently found on the surface of cell walls as receptors that help regulate a number of processes. But, on the negative side of things, they are also a component of cancer cell formation, where these cells build up a large amount of sialic acid compounds on their surface to act as deterrents against immune system cells like natural killer cells. These compounds bind to matching pieces on the NK cells and prevent them from killing the cancerous cells, as they would normally be genetically programmed to do.

Evolutionary Inactivation

With all of that in mind, let’s get back to the study. The researchers were investigating a particular gene that codes for the enzyme CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH). This enzyme, in turn, helps in the synthesis of the sialic acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc). This is a very common compound and is found in most deuterostomes, so vertebrates and all other sea creatures.

However, the gene itself appears to have been inactivated in several animal genomes, including humans, due to a genetic alteration that removed one of the exons and caused a frameshift mutation. This resulted in a enzymatic protein that is only 72 amino acids long and completely non-functional, which isn’t surprising considering the original protein was 590 amino acids long. As such, humans can no longer synthesize the sialic acid Neu5Gc and the small amounts that are found in our tissues are likely obtained from our diets that include organisms that can produce it.

Past studies have implied that the evolutionary reason for this loss occurring and being retained may be because it helps protect us against a variety of pathogens that can only infect organisms by attacking to Neu5Gc receptors on the exterior of cell walls. Sexual selection may have also sped its inactivation, with those women with the mutation having their antibodies negatively target any material with the CMAH gene, including sperm.

This wouldn’t have been helped by the fact that antigens against Neu5Gc in particular are apparent xenoantigens, that is they are antigens that are found across multiple species. And that means other species material can set off an immune response if enough exposure at a high enough rate is encountered.

The Impact On Science

Now, of course, any meat or plant consumption from organisms that express the CMAH gene are unlikely to have any significant effect, not unless consumption of selectively high expression organisms are themselves consumed to excess. Thus, in certain cases and diets, there may be some reason for nutritional concern or be a way to check for someone with an acute sensitivity to Neu5Gc exposure, but it is the other previously mentioned fields that are a greater concern.

Xenotransplantation is an area where knowing whether such incompatibility exists within the comparative genomes is of high consequence and can greatly influence success rates for transplants. Similarly, when using animal models to study human diseases, it is best for them to match the human system as much as possible and this would be one way that the results may not be properly applicable if done in a model that does have an active CMAH gene.

Because of all of this, the scientists at the University of Nevada, Reno ran a full comprehensive analysis on all the genomic data available on the most important animal, fish, and other species, specifically in search for the CMAH gene and its status in the genomes. In total, they looked at 323 deuterostome genomes and found 31 cases where inactivation of the gene had happened. Phylogenetic trees were additionally made to map out the evolutionary history of the gene and where and possibly why it branched off or was inactivated at points in time.

The Sugar Tree of Life

Of these, possible homolog (similar genes by descent) genes to CMAH were found in 184 of the 323 genomes looked into. As just noted, there were 31 independent inactivation events, though only some of them have known explanations, such as in humans and platypuses. 27 of these events are completely new to science and deserve some separate investigation.

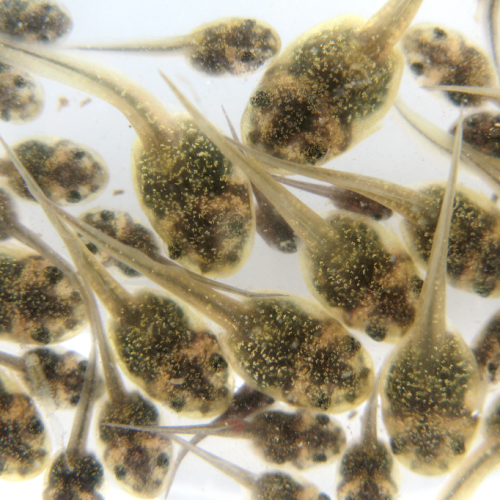

In summary, fish were found to have very low concentrations of Neu5Gc sugars, indicating that their expression of the CMAH gene is equally low, with high amounts only appearing in fish eggs. This means that caviar may deserve some exploration. Birds as a whole lack the CMAH gene from a far past inactivation event, as do reptiles, except for a single species studied.

Within the great apes, humans appear to be the only species that has an inactive CMAH gene. Our genetic incident appears to have solely occurred only in our own ancestry after we split from other species. It’s possible that some other homo sapiens subspecies that went extinct were also after the event, which requires inspection as well.

A New Genetic Puzzle Piece

But those are the genomic results and the somewhat imperative knowledge gained from the study. Hopefully, with this new information, we can further improve both the process of xenotransplantation, but also all model organism research into human conditions too. Furthermore, revealing the CMAH gene’s impact on cancer cell spread and how lack of the gene offers protection against any number of pathogens can help further disease research and the role particular genes play.

The history revealed by this study is yet another step on the genetic road-map for science and medicine.

Photo CCs: Spiral timetree from Wikimedia Commons