The diversity of life on Earth is staggering to attempt to comprehend in its entirety. And the species that we are already aware of likely are but a fraction of the true multitude still to discover. This is especially so for the most numerous group in the kingdoms of life: bacteria.

A Lack of Gene Enlightenment

We just have no real way of knowing how many bacterial species there are out there in the world. The one we have found, largely due to how they affect humans in some way, are probably just a blip in the true broader spectrum. Currently, a significant restriction on our ability to find them is our inability to culture many of them, to be able to grow them in a lab and obtain pure cultured lines that can be described and seen to be new species.

But even within the bacteria that we have already found, there is still much work to be done. While we know they exist, we know very little about their genetics. Proper genetic sequencing that is able to process a genome in a short period of time remains a very new technology and, thanks to that, our focus has largely been on selected bacteria that we need to know more about for scientific research or medicinal experiments.

A Dearth of Exotic Sequencing

Researchers at the United States Department of Energy’s Joint Genome Institute had concerns that this selective sequencing of bacteria was leaving a huge gap in our understanding of bacterial genetics. As they noted, in 2015, 43% of all the bacterial genomes that had been sequenced that year made up just 10 species in total. This was due to multiple different strains being sequencing individually for disease research.

And while this is important, such biased sequencing is interfering with our mapping of the phylogeny of bacteria and greater descriptions of how their genomes function. Working within only a narrow band of bacterial species limits the kinds of genes, proteins, and other cellular components that we are aware of. It has long been shown in other kingdoms of life that farther apart species in the tree relate to the finding of new genes and proteins altogether.

The scientists decided to fix this. When they began their experiments in December of 2015, there were over 12,000 known bacterial and archaeal species, just on the verge of 13,000. But there were only 826 sequenced genomes available, many of which were for different strains of the same species.

A Grand Undertaking

So, they started a pilot project called the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea (GEBA). Originally, they released 56 new type strains from more far-flung bacteria, serving as a proof of their claims on finding new genes and proteins. Now, they have released something far larger.

As a part of the first release of the project titled GEBA-I, the scientists have sequenced 1,003 genomes. To quote them, this included “974 bacterial and 29 archaeal genomes (from 579 genera in 21 phyla and 43 classes)”. In addition, this involved 396 genomes that were in a genus that had never been sequenced before, offering entirely new information. They also made sure that the sequences weren’t all from the same environment. Samples were obtained from human environments, the wild, and even places where extremophile bacteria live.

The biggest and greatest point is that, being a government-run project, all of these genomes are now in the public domain, available, and easily referenced from the project’s database. The data includes 3,402,887 gene sequences for encoding proteins. When compared against the 23 million already known protein gene sequences of bacteria and archaea, the researchers found that more than 10% of the genes were for entirely new, never before seen proteins.

Long Road To Walk

There are many other impressive findings through genomic and metabolomic analysis of the data, but it’s far too much to cover here. If you’d like to learn more about the genomes sequenced, you can look at the open source study linked below.

For now, just know that the Joint Genome Institute is working hard to find new breakthroughs in the field of bacterial genetics and who knows what uses will come out of the genes and proteins they uncover. As usual, only time will tell.

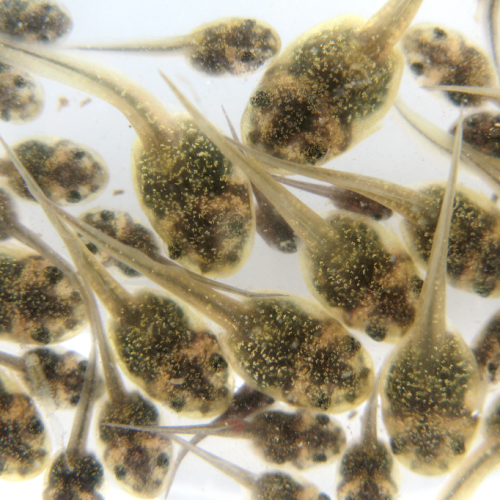

Photo CCs: HeLa-II from Wikimedia Commons