Proteins make up everything living that matters. Okay, sure, DNA actually makes up everything, but DNA just exists to transcribe and make proteins.

It’s the proteins that actually get the work done. All the tiny cellular work that eventually causes macroscopic bodily changes. So, give proteins a little thank you every once in a while.

Proteins: How Do They Work?

Unfortunately, proteins are, like the rest of our body, not immortal. They have a shelf life and have to be replaced once they run down their physical chemical shells. But how often does this have to happen?

One would guess that different types of proteins probably degrade at different rates. I mean, at minimum, they’re not all the same size. Some proteins can be made up of just a handful of amino acids linked together, while others form complex 3-dimensional wrapped structures using hundreds of amino acids.

But even with that understanding, how often are we talking? Since our cells have to expend energy to queue up a replacement protein and that could possibly be a large drain on energy.

The simple answer is we don’t know. Well, we know some of it, but most of it still remains a mystery. Proteomics is still a baby field, after all. And while it is growing rapidly alongside partnered fields like epigenetics and metabolomics, there is still much work to be done.

That’s Why We Have Scientists

Enter the University of Western Australia.

Researchers there have been investigating the very question of “protein turnover” in plants, otherwise known as the rate at which plant cells have to churn out replacement proteins.

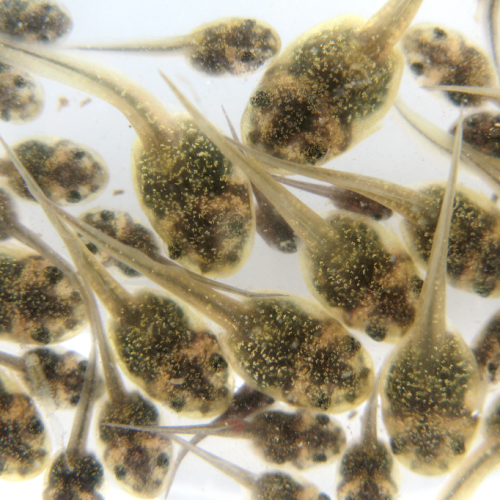

Utilizing new 15N labeling methods, they have been able to explicitly quantify the energy required to make that new protein, the so-called energy investment of the cell. They, in addition, have determined the rate of turnover for over 1000 proteins present in the model organism Arabidopsis.

What they’ve found is that the numbers vary by quite a lot. Some proteins only last for a few hours, completing their task and then falling apart. Other proteins can last for a period of months, if they have longer-lasting jobs assigned to their structure.

All of this was largely based on the highest level of protein conformation related to complexes and domains in folding.

More Knowledge, Better Crops

The hope is that with a better understanding of all these mechanisms, scientists will be able to manipulate and change the genes behind them, effectively “teaching” the plants to be more energy efficient.

This is due to the fact that while evolution and natural selection may produce fairly efficient organisms, it isn’t perfect, not by a long shot. Which is to be expected from a system of randomness and trial and error.

Stricter energy efficiency in plants will allow them to better regulate and use that spare energy for other purposes, such as growth. This, in turn, could result in faster growing times and higher yield in the long run.

For now, researchers want to focus on getting down into the details of how proteins function and see if all of them are truly needed in the engine of life.

Photo CCs: Arabidopsis thaliana inflorescencias from Wikimedia Commons