Among all the plant diseases and pests that those in agriculture face, it is often the viral-based conditions that prove the most troubling and difficult to manage.

Unlike weed or insect-based attacks that can be combated with various types of pesticides or direct action, viruses have no explicit counter when working in agriculture. Vaccines for plants are limited in faculty and largely only useful for bacterial diseases.

Breeding or genetically modifying resistance against viral plant vectors usually becomes the only option. But unless one is going to just try shooting in the dark, enough has to be known about the virus in order to develop a response.

That’s where our old friend genetic sequencing comes in.

The Background

We’ve discussed the Potyviridae family of viruses before on Bioscription (https://goo.gl/nIde0P) and they return as a topic today to target wheat crops in the US and around the world.

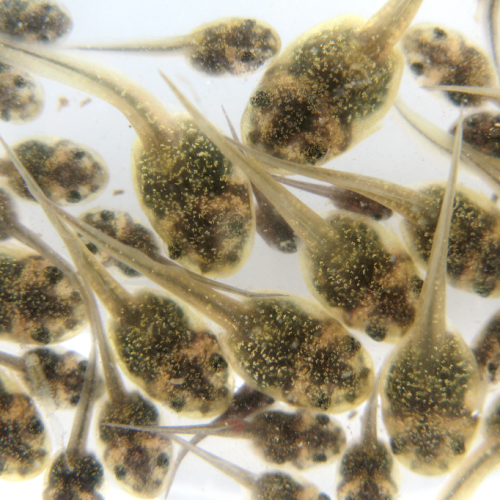

Researchers at Texas A&M University have been using genetic mapping to better understand the wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV), a deadly disease-causing virus in wheat that has been known to have a 100% mortality rate in a year’s crop. While it does have a sometimes vector in the form of the wheat curl mite, which can be killed, the virus itself is insidious and takes its time to emerge and then stays within grasses and crops all year-round. This makes its emergence unpredictable and eradication of all of its occasional mite transference hosts is not a practical solution.

More concerning, it synergizes with other mosaic viruses in order to become even more virulent. Developing some form of resistance against it in wheat is a high priority for crop scientists in many countries, since there is no known method for chemically stopping its spread once inside grasses and crops.

Finding Resistance In The Haystack

For that purpose, the A&M researchers have been looking into the Wsm2 gene that has been known to give wheat resistance. They have gathered different wheat lines from across the United States as different resistance sources. This ultimately left them with two genes of consequence, Wsm1 and Wsm2.

In order to isolate the stronger bred wheat that has these resistance genes, the scientists have been using marker-assisted selection focused on the 8 single nucleotide polymorphisms that surround the Wsm2 gene.

A specifically designed PCR system nicknamed KASP uses those 8 markers in order to screen through the thousands of wheat lines sent to them in order to determine which ones have the resistance genes.

This, in turn, allowed those lines with resistance to be interbred into those without, resulting in dozens of breeding lines in production to counter WSMV’s infectious spread.

The March Continues

Whether this resistance gene will be enough to completely beat back the virus has yet to be seen. It’s possible that new strains of WSMV will emerge that can get around the Wsm2 gene and the entire process will start over.

But even in the endless agricultural fight against nature, it’s quite clear that human ingenuity and the power of modern biotechnological science is slowly prevailing.

Photo CCs: Weizen2 from Wikimedia Commons