Just because new techniques and technologies are developed doesn’t mean the oldies aren’t still as useful as they were before.

Today’s topic is related to the topic of de-extinction, in that the methods used are actually quite similar. And since this topic is being used to save the populations of rare and endangered birds, I suppose de-endangerment would be the appropriate term.

Sorry, Mammoth Fans

In de-extinction research, there are multiple trials that must be overcome if there ever is going to be any success and, depending on which creature one is trying to resurrect, some may not be possible to surpass in the first place.

Take the most popular example of the woolly mammoth that has had several decades worth of research go into finding a way to return it to life. What have been the results of all that time and effort?

That it’s not possible.

There just isn’t enough intact DNA from the mammoth genome to use after so much time, it’s degraded far too much. Even in the most perfectly preserved specimens, the best you’ll get is bits and pieces of genes, as the cells undergo apoptosis and lysosomal autophagy whose very purpose is breaking down the DNA in the cell.

But There Are Alternatives

So, instead, the researchers involved in that and related de-extinction focuses have turned to using the bits and pieces of genes they’ve recovered to modify the closest living relative of the species to be more like the ancient one. In the case of the mammoth, that means modifying an Asian elephant to have long fur and other characteristics akin to a mammoth.

But make no mistake, none of that makes an Asian elephant a mammoth. It just makes it look visually similar, but all it is is a genetically modified elephant. This process cannot accomplish true resurrection.

Not for a species that old, at least. More recent examples, such as the passenger pigeon, have a far greater chance of being reborn from scientific endeavor.

Onto The Actual Topic

Back to de-endangerment though. Researchers at the University of Edinburgh have focused on genetically modifying chickens to be able to produce eggs from other bird species, including rare bird breeds.

For this process, they used an older gene editing technology known as TALENs (Transcription activator-like effector nuclease) that essentially work like other restriction enzymes by always cutting specific parts of DNA that is pre-determined. While not as versatile as CRISPR and only able to cut genes rather than insert them, it is still a valuable tool for quickly cutting out desired genes.

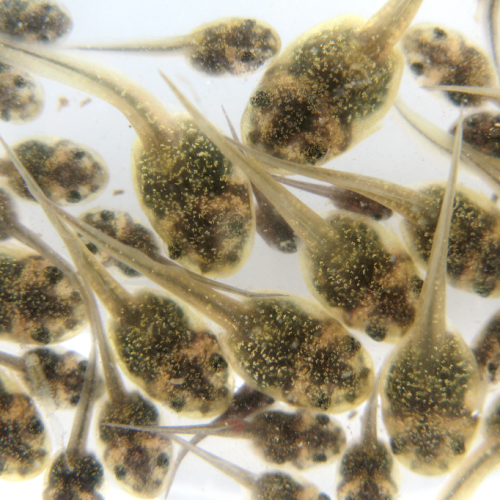

The scientists took a group of commercial hens and used TALENs to cut out the DDX4 gene, which is responsible for producing primordial germ cells that ultimately lead to eggs. With only this change, all they had really done is make a batch of sterile hens, but this is only step one of the plan.

The next step for any researcher that wants to continue with the experiment is to decide which bird breed one wants to create and then insert donor primordial germ cells from that species into the hens. The eggs the hens produce would then be genetically identical to the donor bird instead of the hen.

Limits For The Future

One obvious restriction to this process is the size of the donor bird. Trying to implant, say, eagle donor cells into the hens likely won’t turn out well for anyone involved. Sticking to similarly sized or smaller birds to implant is the best bet, though there is always the possibility of rejection depending on how closely related the donor bird is to the hens themselves.

The researchers have stated that they are only going to use the hens at this moment for increasing the biodiversity of chicken stock worldwide and increasing the amount of rare chicken breeds. But there is still the capability of expanding that to other birds besides chickens in the future.

Either way, this is both a step forward in genetic modification efforts (especially because these are the first GM birds to be made in Europe) and in protecting endangered bird species, even if just chickens for now. Hopefully future experiments will be able to make full use of these egg-less hens and perhaps even in ways not foreseen right now.

Photo CCs: Take five! from Wikimedia Commons